Labour's response to the crisis

GDP figures show recession deeper than thought

It is not great news for any government to find that its economic policy has been discredited. The latest GDP figures showed the economy shrank again last quarter, by 0.7 per cent. That must be particularly hard to take for a coalition government formed, it was claimed, to sort out an economic mess. It is worth taking a look how Labour can develop a credible response to the latest phase of the economic and financial crisis.

The GDP figures represented the preliminary estimate. It is based on incomplete data and relies on surveys for the month of June. It is therefore subject to revision in later estimates and the final figure can take months or years to come in. This quarter saw two bank holidays in June and only one in May, which may have distorted the initial figures. It also rained a lot, which may have depressed economic activity. Nevertheless we should not be that surprised that GDP was weak to say the least. Bank of England governor Mervyn King in his Mansion House speech in June noted that economic conditions had deteriorated significantly since the bank published its last inflation report in May. The latest leg of the eurozone debt crisis hit economic confidence and it would be a surprise if that did not affect the UK economy. UK businesses and households face challenging times. This is compounded by a government with little practical will to stimulate growth, which has cut public investment, and which is now making severe cuts to current spending. The government has another problem: its U-turns have raised questions about whether it can see through the spending cuts it has planned. If not, the UK’s AAA credit rating could be threatened, some believe.

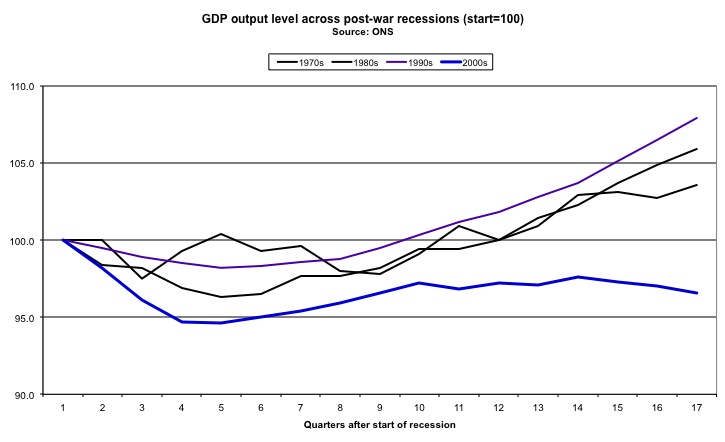

An interesting chart published by the Office for National Statistics plots the current downturn against the previous three recessions. Much of Labour thinking is still dominated by memories of our reactions to the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s. The chart shows that, in contrast to those recessions, the economy this time has yet to recover and is in fact going backwards. We can still say this if the Q2 figure is revised upwards. The blessing is that unemployment has not risen by so much. We are in depression territory and face a prospect of low or no growth for a long while to come and certainly if government remains passive. Making policy in this environment is very difficult.

The policy response relies on quantitative easing by the Bank of England, which recently announced another £50bn of gilt purchases. That has helped lower gilt yields, with the 10-year gilt dipping below 1.5 per cent. The Bank of England also took action in the money markets to increase liquidity, which has lowered short-term interest rates. The IMF, in its latest report on the UK, argued that if monetary policy does not work the government should slow the pace of fiscal tightening. It believes that allowing a larger deficit than planned will have little impact on bond yields (ie the cost of government borrowing). It notes in support of this view that when George Osborne had to ease his plans for structural adjustment last autumn there was no market response. The IMF may be suggesting a wise course of action but the Tory-Lib Dem strategy presumably remains to generally sit tight and see through a politically very bad year, hoping the economy will recover in time for the next election.

UK citizens have experienced years of incomes being eroded by inflation. Increasing energy and food costs have meant there is less income for other things. With a lower oil price and no new taxes it may be the case that income available for discretionary spending begins to rise slightly. That might improve sentiment a bit. Moreover, there could be a small growth rebound in the third quarter.

It is difficult for Labour to agree with the IMF line that some fiscal relaxation may be required because the economic debate remains on deficit-cutting territory and Labour is regarded as responsible for much of our economic predicament. Unfair though this is, it remains the view of many. But events may prove Labour right sooner than we think. While consensus (and, with it, probably government policy) shifts, Labour still needs to build credibility on deficit reduction while focusing on the big themes about the future – jobs, investment – and linking them with the experience and aspirations of individuals and families.

This article was first published by Progress on 26 July 2012.Progress, 26 July 2012, 29/07/2012