Budget 2017: missed opportunities

The story of the autumn budget this year is one of missed opportunities combined with a very big reality check. We should embrace it as cathartic. It is only by recognising the extent of the challenges facing the UK economy that we can begin to formulate policies which are worthy of them.

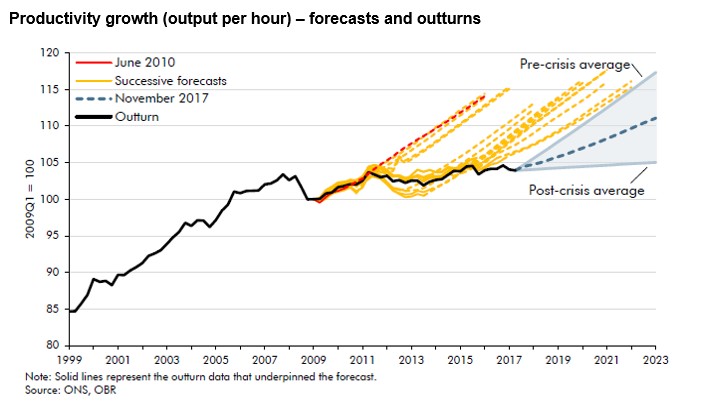

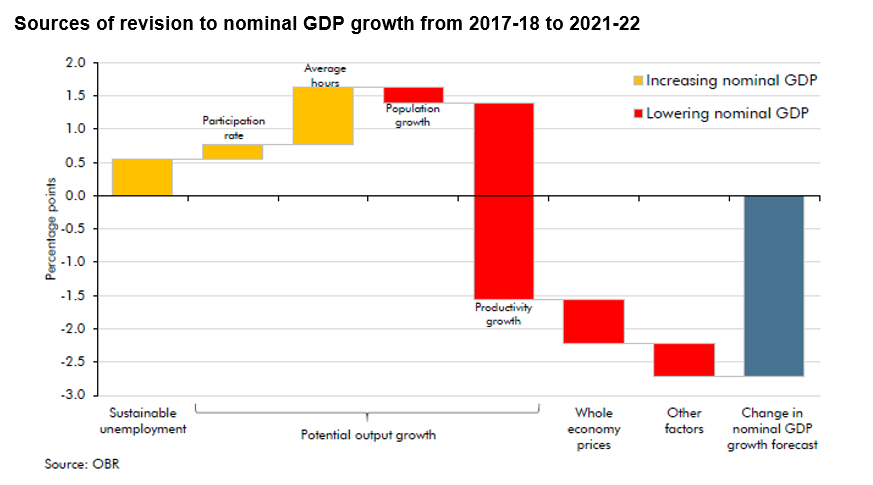

The budget was presented against the backdrop of significant downward revisions to growth forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). These were primarily driven by new assumptions about productivity growth. Before the financial crisis productivity, as measured by output per hour worked, grew on average around 2 per cent pa. Since the crisis, the OBR has generally assumed that productivity growth will eventually rise back towards that level. The problem is that it has not. Productivity matters because it is what drives real wages. It also drives GDP growth, without which we need to rely on working more hours or employing more people, which cannot increase indefinitely. The OBR has concluded that growth in productivity and GDP will only be around 1.5 per cent pa long term, and even this forecast for productivity growth is above the average seen since the financial crisis.

These figures are only forecasts. However they are important because they feed into tax and borrowing projections. Lower growth means lower tax revenue and hence higher borrowing. The OBR has stopped hoping we will return to pre-crisis normal anytime soon. After the crisis, GDP fell but spending was maintained and so increased considerably as a proportion of GDP. Yet the crisis exposed fundamental flaws in the UK economy and put a severe dent in our productive potential. The economy shrank and we could not maintain pre-crisis spending levels without borrowing or growing. That is what so-called austerity has been about.

The OBR forecasts with this budget show that we are in a bigger hole than our political class has believed since 2008. This is the big reality check, and yet politics is still catching up. It affects everything government does. It even affects Brexit, since our negotiating position would have been considerably stronger if our economy had been in better shape. But then in that case, Brexit might not have been happening.

The answers are not easy to come by, even if we want those answers should be bold. We cannot simply continue borrowing without regard for fiscal targets. While interest rates are relatively low at present and the maturity of UK government debt relatively long (which means interest rate rises take a while to feed through substantially into higher borrowing costs), a shift in financial market sentiment, combined perhaps with an inflation surprise and government chaos could push borrowing costs higher. Markets need some sense that public borrowing is under control. While a government could get around the problem by printing money, this carries risks not least because it could drive down sterling and so push up prices.

However, a lack of growth is a problem for all concerned, markets included. It is therefore possible to increase levels of borrowing to fund investment spending. The OECD has noted that the UK has significant infrastructure investment needs compared to other advanced economies so in theory there should be plenty of opportunities. Indeed, as the Institute for Fiscal Studies has noted, the chancellor’s plans will push investment spending to 2.4 per cent of GDP, which apart from a spike just after the financial crisis, would be the highest share of GDP for forty years.

It would have been better if the Conservative led governments had prioritised growth from the beginning. That way, we would have been more likely to avoid years of spending cuts and squeezes. Instead we have had missed opportunities. Yet we cannot go back in time. Policy development needs to focus around the following:

-

Increased public sector investment combined with strict rules on where we invest

We need more infrastructure investment throughout the country, but it is tempting for government to dress up current spending as ‘investment’. Do that and we undermine our efforts to boost long term growth.

-

More effective public spending

We should not need spending restraints to remind us that government spends people’s money and not its own. The task is to promote the common good when doing so. That means spending wisely and a proper debate about how we run our public services.

-

Dispersion of technological gains

We could be on the cusp of another technological revolution. While it can take longer than expected for invention and innovation to make an impact, there are measures we can take to help it happen. It is right that innovators are rewarded for their work and risk-taking. Yet this should happen without significant monopoly power accruing, which can stifle growth. We cannot pick the winners but we can ensure everyone has a stake in future innovation.

-

Stable environment for business

Business investment growth is low. The latest GDP figures show this has not changed. Businesses and investors need a stable tax and regulatory environment in which to make long term decisions. Brexit acts strongly against this but within that constraint we need to create a clear and simple vision for business in Britain.

-

Get ready for the demographic shift

It is already happening but the effects are not all negative, as some appear to suggest. Still, it means we need to anticipate the powerful economic forces involved.

Fabian Society, 24 November 2017, 24/11/2017